- Home

- Richard Hamilton

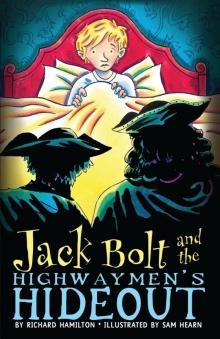

Jack Bolt and the Highwaymen's Hideout Page 2

Jack Bolt and the Highwaymen's Hideout Read online

Page 2

“Sorry, sir.”

Jack couldn’t move. Caught between astonishment and fear, he watched as the man with the wig crawled through the hole in the wall into his bedroom. He held a candle and was dressed in a long waistcoat with an extravagant lace cravat, white riding breeches, and black leather boots. Incredibly, his eyes passed right over Jack, sitting in his bed in the shadows.

“This hidden cupboard is large enough for ten men to hide in. The soldiers would never find us. Not in a month of Sundays.” The tall man spoke with pleasure.

“The soldiers could be having a cup of tea downstairs and not know we was here!” laughed the second man. “This room is above the pigs!”

“Impossible!”

“Oh, my lord! This is witchcraft!” The short man shuddered.

“Rubbish—”

“It is a terrible magic,” he whimpered.

The tall man now held up the candle. He looked from the curtains to the closet to the bed—and suddenly he locked eyes with Jack.

“BAH! Dash it—a BOY! Whaaaaa!”

He dropped the candle, which hit the floor and went out, plunging them into darkness.

“Get off! My lord! Whaaaaa!”

There was a snap, a thud, and a splintering of wood as the two men fell over and smashed the chair. Panic seized them and there was another bump as one of them blundered into the closet.

Jack leaned out of bed. There was no time to think. He turned on the bedside light.

Click.

Light burst on to the scene, as shocking as an explosion.

The men froze. The tall one with the curly hair and the fine cravat was sprawled on the broken chair, his eyes popping with surprise; the short scruffy man was caught up in the curtain, holding it so hard that there was a slow plinking noise as he pulled it from the hooks. Plink, plink, plink.

In the bright light, they were both thoroughly exposed.

“Who are you?” stammered the tall man.

“I’m Jack Bolt,” said Jack, with a steely control. He breathed deeply, evenly. He was worried his voice might falter. “Who are you?”

The tall man lay blinking in the light—he gazed at it with deep suspicion as he struggled noisily to his feet. He brushed himself off and adjusted his wig. At last he announced in a hushed, self-important tone: “I am Lord Henry Vane. Highwayman of glorious fame. Your servant,” he said with a bow.

“And I,” said the man still gripping the curtain, “I am Tom Drum. His servant.”

Chapter Five

A Loop in the Ribbon of Time

“Jack! Are you all right in there?” It was Granny, calling from the landing.

“Yes.”

“What did you say?”

“YES, Granny!”

“I heard a bump—”

“I’m okay! I fell out of bed.”

“You fell on your head?”

“BED! I fell out of BED.”

“Oh, good. I’m going to bed, too.”

Jack didn’t tell his granny about the visitors. His first thought was to call out, to get her to come in and rescue him, but then the tall man—Henry Vane—glared at him and put his finger to his lips. Jack understood: this was a threat. Then the man took out an antique pistol. This was a serious threat.

“Good night, Granny!” Jack called.

“Good night.”

Henry Vane smiled. It was quite a friendly smile, for someone holding a pistol. “Good boy, Jack Bolt,” he said in a low voice. His eyes were drawn to the light by Jack’s bed. He gazed at it as if it were some dangerous magic.

“What are you doing in my bedroom?” Jack asked.

“No, Jack Bolt,” retorted Henry Vane, adjusting his hair, “what are you doing in my … cupboard?” He stroked his cheek with the antique pistol in a thoughtful way.

“Looks like a bedroom to me,” Jack replied. These men are weird, Jack thought. All dressed up as if from another century. Despite the threatening pistol, there was something almost funny about them. It was as if they had stepped off a stage or out of a movie screen. It was strange: for some reason they appeared confused and frightened by Jack. That was good, he thought; it gave him courage.

Lord Henry Vane’s nostrils quivered. He kept looking around the room as if he couldn’t believe his eyes. He obviously didn’t like being contradicted. “It’s a cupboard,” he insisted, stubborn in the face of the evidence. “A large cupboard, almost like a room. Beside the fireplace in Nanny Manners’s house.”

“With a bed,” Jack pointed out, “and a closet and a chest.” He didn’t have a clue who this Nanny Manners might be. “I’m telling you: you are in my granny’s house, where I am staying.”

“… In the cupboard above … the … pigs …” The man by the window, Tom Drum, seemed panicky. His hands were trembling.

For a moment Jack wondered if they were a crazy historical reenactment group, like the ones he’d seen at a castle once. Enthusiasts who liked to dress up in clothes from the past and do spear-fighting demonstrations … or maybe this was some awful TV hoax?

Tom Drum took Lord Henry’s arm. “Consider, my lord,” he whispered, “that this is not a boy? Eh? This is an angel?” He pointed a dirty finger at Jack. “Look at his pearly skin and strange yellow hair. And his garments … what are they?”

Jack glanced down at his pajamas. They had a winged motif on the front and the words “Motorcycle Heaven” printed in a gothic script. His pajama bottoms were plain red cotton. What was wrong with his skin? At least it was clean—these guys looked like they needed a shave and a serious wash.

“No. He’s got no wings,” said Lord Henry, peering at Jack as if he were a freak.

Jack didn’t like being a curiosity. Especially when they were the strange ones.

“When you say that you’re a highwayman,” he asked as casually as he could, “do you mean that you are robbers?”

Both men smiled, which unnerved Jack. Tom Drum had a gap-toothed grin; Lord Henry had a wide, white, winning smile—the too-good-to-be-true, heart-melting smile of a charmer.

“We are robbers,” Henry Vane told him grandly, puffing himself up like a peacock. “But no ordinary foot padders: we are gentlemen robbers, on horseback. There’s a world of difference.” He picked up Jack’s toothbrush and idly studied it. He’d never seen one before. What was its use, he wondered.

“Well, you’re housebreakers now,” Jack pointed out.

“Watch it, boy!” Lord Henry’s smile vanished. He stabbed the air with the toothbrush, pointing it at Jack. “Housebreakers are very low. Highwaymen have considerably more standing! They are sneaky; we are daring!” He tossed the threatening toothbrush aside; it landed silently on the bed.

“Sorrrreee,” said Jack. They’re quick to take offense, he thought. “Where are you from?” he asked.

“Here and there,” replied Henry Vane, running his fingers through the frill on the edge of the lampshade. “We appear out of the darkness when we are least expected. And where are you from, Jack Bolt?”

“London,” Jack replied straightforwardly.

“But that’s not London speech.” Henry Vane raised an eyebrow.

“Well, I live there.”

“Where, exactly?” The highwayman challenged him.

“Holloway. Near the subway station.”

“Holloway-near-the-subway-station? I know London—and I know it well—and there is no such place,” he asserted, his eyes narrowing. Before Jack could reply, there was an outburst from Tom Drum at the window.

“Lord a’ mercy! Look, my lord! The houses—they have multiplied. The pigs … gone! The cooper’s house and Old Ma Cracklepot’s—gone! Oh, my lord—we have been bad and now some wicked spell is on us.”

“What are you squawking about, Tom?” In a stride Lord Henry joined Tom at the window and looked out. He clasped his hand to his heart.

“Blood and thunder!” he swore. “’Tis London! No—look: there is the Cap and Stockings. But—all else is changed! So m

any houses. And lights. Maybe you are right, Tom—the devil is abroad! Where can this be—Jack, tell me!” he demanded.

“The village? It is called Wittlesham.” Their tone made Jack uneasy. He began to feel dizzy, as if a great space had opened in his head.

Lord Henry nodded. He breathed deeply, in and out. He seemed to struggle with an idea and for the words to express it. “It is Wittlesham—but—the farms are gone, the houses altered …”

Through the dizziness, a thought came to Jack—and the world seemed to somersault: these men were not pretending to be from the past. They were from the past—he knew it.

“What date is it—where you are from?” His voice shook.

“The thirtieth of October.”

“No—the year. What year is it?”

The men looked at each other and at Jack. “Year of our Lord: 1752.”

“Really?” Jack asked, his eyes wide. “I mean really REALLY?”

“Indeed. Really, REALLY,” replied Henry Vane, bristling. His hand slowly rose to his brow.

“You are now at the beginning of the twenty-first century!” Jack exclaimed. “You have traveled forward in time over two hundred and fifty years!”

The men did not understand. Jack watched their faces struggle with the idea.

“Piffle!” said Lord Henry at last.

“What does that mean—‘traveled forward in time’?” Tom Drum was bewildered. His mouth opened in a big O. “On what?”

“It is a monstrous idea,” said Lord Henry. “An abomination!”

But Jack was now convinced. “It happens all the time in the movies,” he told them excitedly.

“The whats?” Tom Drum was mystified.

“And on TV.”

“On what?”

“It could never happen.” Lord Henry looked desperately around the room. “Impossible.”

“Did you have electric lights like this—or toothbrushes—or plastic bags or footballs—or ballpoint pens—did you have them in 1752?”

The men were silent. Henry Vane’s eyes darted around the room. He stared at the things Jack pointed to.

“Did you have cars and trains and planes?”

The men frowned. They did not understand such things.

“Did you have—”

Lord Henry held up his hand, looking back at the hole in the wall through which they had appeared and then to the room where they were standing. His voice shook. “It may be that some strange thing has happened—that time is out of joint and all awry—I know not. Nor does it matter. But, but this I do know …”

“How is it, my lord?” interrupted Tom Drum, holding his head as if the thought hurt. “I don’t understand!”

“Imagine, Tom, a ribbon.” Henry dug around in his pockets and pulled out a black ribbon, which he held up like a magician. “A long ribbon of time. Think of the years stretching out across its length. And then suddenly the ribbon doubles back on itself and two parts—two different times—touch.” A confidence lit up Lord Henry’s eyes as he made a loop in the ribbon. “Our time and Jack’s time have touched. Now—we are in that loop and somehow, somehow, we have passed through from one time to the other. Is it so?” he asked Jack.

“In a nutshell.” Jack grinned at the elegance of the explanation as his mind reeled with the possibilities.

“Yet it matters not one bit … for this,” continued Henry Vane, delighting in a brilliant idea that was just dawning on him, “this is the very best hideout in the land. Why, Ali Baba couldn’t have wished for a better cave to hide his loot in! And Jack, Jack Bolt … the Keeper of the Hideout—you will keep our secret, eh? You will look after our loot? For we shall pay you handsomely for the use of your bedroom! In golden guineas and so forth. Only you must tell no one. Eh? Not even the granny—what do you say?”

“Okay,” Jack said guardedly. He wasn’t sure if this was the right thing to do, but he had no choice.

“O. K.” Henry Vane frowned. “O. K.? Is that yes or no? I have no ‘O. K.’”

“It’s ‘yes,’” said Jack.

“Then we bid you a good night, Jack Bolt,” said Lord Henry abruptly. He bowed elaborately, then backed out through the hole, pushing Tom Drum through first. “We have work to do, Jack—important work. But we shall be back. We shall be back,” he said and winked as he closed the hole in the wall.

Jack lay still in his bed. He waited until there was silence, then stepped over to where the strange men had disappeared. The wallpaper was torn and messy, as they had crawled over it from the other side. It must be some sort of door, he thought and gave it a push.

It wouldn’t budge.

Chapter Six

The Other Time

“I’ve got a very busy day, I’m afraid,” said Jack’s granny at breakfast the following morning. “And I expect you do too?”

She looked at Jack with beady eyes. She always made him feel that she could see right through him. Her gray hair was cut short and her beaky nose and blinking eyes made Jack think of a smart bird. She had provided a hearty breakfast of oatmeal and a boiled egg and toast. Now she was expecting an answer.

“I’ve got a lot to do,” Jack told her loudly.

“Good,” boomed Granny.

Jack chewed his toast. I had a couple of highwaymen in my bedroom last night. They popped through from the eighteenth century. He practiced saying it in his head. He could say it now. Obviously Granny wouldn’t believe him. And then he could take her up and show her … what? The mess?

“You know how to reach me,” said Granny. My cell phone number is by the phone. I’ll be back for lunch. If you get hungry—help yourself. There’s ham and quiche in the fridge.”

Jack opened his mouth as if to say something, then closed it. Sometimes busy grown-ups miss the most exciting things.

Back in his room, Jack looked at the mess. There were black footprints on the wallpaper, and the candle had made a waxy splotch on the bed. The chair was broken and the curtains were ripped off their hooks. Oh, dear. What would Granny say?

Then he saw the bag that the highwaymen had left, lying by the old chest. In all the excitement, he had missed it. He opened the drawstring and looked inside. There were silver knives and a silver jug, a bag of coins, and some rings and a necklace. Wow! Treasure! Real treasure.

He reexamined the wall. First thing in the morning he had tried again to open it. He had picked at the wallpaper and found a sheet of rusty metal with hinges at the bottom. He had pushed it, but it wouldn’t move. He wondered—had it always been here—only just now discovered?

Looking again, he thought he could see a sliver of light at the side. He found a metal coat hanger and began working the hook along the top edge, sawing in and out as the knife had done the previous night. Suddenly the door fell open. “Yes!” Jack clenched his fist in triumph. Then, blinking through a small cloud of dust and plaster, he peered through.

The metal door had fallen to the side of a fireplace on the other side of the wall. As the dust settled, he could see into the room beyond. It was a room he had never seen before.

Smaller than the room in Granny’s house, it was darker and dirtier. Jack could see a rough, unmade bed and a wooden chair with clothes on it. He felt fluttering butterflies in his stomach. Could he really be on the brink of the eighteenth century?

Then the smell hit him. Wood smoke and pigs! It stuck in his throat and made his eyes water. Still, he took a deep breath and crawled through. The whole world changed. The house was suddenly utterly silent, as if the low buzzing of modern life had been wiped clean away. Here was a deep country silence, without electronics or machines or passing aircraft.

He found the room basic and bare. There was a small window low down on his left. On his right, there was a candle on the floor with a cascade of drips around it. A black coat hung on a hook by the narrow door. It felt like a different house.

Gradually he became aware of sounds. He heard a crowing far off, a squawking of birds, a grunting and snuffling of pigs

. It was as if he was in a farmyard. A voice outside startled him. The accent was so broad and unfamiliar that he couldn’t make out what was being said. It sounded like: “Saaaf. In the faaarrrmy.”

He peeped out of the dirty little window.

“Oh, wicked!” he breathed. The view from his bedroom window, of the little market square with trees and benches and a clean black road running around neat little houses and shops, was completely transformed. There was mud everywhere. The houses were small and dirty. Ducks and hens roamed freely; a horse and cart stood waiting.

But there was the pub! The Cap and Stockings! It was immediately recognizable with its row of three dormer windows and the jutting-out window by the door. It was dirtier and poorer and had ivy growing up one side, but it was unmistakably the same building.

A man appeared at the far end of the square. He was wearing a smock and rough peasant clothes. Jack watched him put a wooden box on the cart, then he disappeared around the corner of a building. An everyday scene of the eighteenth century—just a man loading a cart.

Jack crept to the door of the room, past the unmade bed and a leather bag stuffed with clothes that spilled out onto the floor. He saw the arm of a man’s shirt trailing across the floorboards, and he caught a glimpse of a gold button nestled in dark folds of velvet. He couldn’t help feeling he was in an entirely different house but had to remind himself that he wasn’t. This was still Granny’s house! So he wasn’t doing anything wrong, was he?

He opened the small door and found a narrow staircase. There was no staircase here in Granny’s house. But it must lead down to the kitchen. Jack listened. Nothing. The first steps creaked dreadfully. As he expected, there was the kitchen, smaller and darker than Granny’s. Looking through the simple oak banister, he could see a table and two chairs and the big fireplace with a fire slumbering and pots and pans stacked nearby.

Jack stepped off the last stair. And something hit him.

Chapter Seven

A Knotty Problem

Jack Bolt and the Highwaymen's Hideout

Jack Bolt and the Highwaymen's Hideout